History

The Hamada Silkworks (Magnenerie Mourgue d’Algue)

The Hamada Silkworks, renowned for producing some of the finest silks sold worldwide, first opened its doors in 1851. This establishment marked a significant shift in Lebanon’s social and economic landscape, introducing silk production as a key industry. French spinners were brought in to train local women, leading to a social revolution in this traditionally rural area as women began working outside their homes.

The transportation of silk cocoons and finished silk from Beirut’s port to Marseille laid the groundwork for maritime transport agencies in Lebanon. Similarly, loans to traders and intermediaries for purchasing silk cocoons from farmers led to the creation of financial trading posts and eventually contributed to the establishment of the first Lebanese banks and the development of the port of Beirut.

The increased demand for silk textiles in France during the 19th century, particularly after blights decimated European sericulture, made Mount Lebanon a vital source of silk. European silk manufacturers sought alternatives to the dwindling supplies from France and Italy. The establishment of silk mills in Mount Lebanon was driven by this demand, with French industrialists setting up operations to meet their needs. The introduction of European silk-spinning factories significantly boosted the local economy and industrialized silk production in the region.

“Increased weaving of silk textiles in France in the nineteenth century required more silk thread than could be supplied by European sericulture. This was especially the case after 1865, when blight decimated French and Italian sericulture; industrialists of Lyons and Marseilles needed to find alternative supplies for their factories. The presence of European silk-spinning factories in Mount Lebanon, regular and inexpensive steamboat service between Beirut and Marseilles, diminution of tariffs and customs on exported silk thread, and the rise of French political prominence in Lebanese internal affairs after 1861 convinced these industrialists to choose Mount Lebanon as one source of silk. For the peasantry, increasing production of silk and selling it to the French made economic sense. While in the 1840s the price of one Okka (1.228 kilograms) hovered around 12 piasters, by 1857 French merchants were paying 45 piasters per Okka, and those prices persisted with minor changes through the 1870s.

While French need for cocoons occasioned the proliferation of mulberry trees and sericulture, French demand for silk thread encouraged the industrialization of silk spinning in Mount Lebanon. Before 1838, silk spinning in the Mountain was carried out by Hilalis (itinerant spinners), who used a hand-powered spinning wheel which the French called Roue Arabe. However, French silk factories required a stronger and more evenly spun silk thread than could be obtained using these traditional methods. This convinced some European entrepreneurs, bent on profiting from satisfying the requirements of French industrialists, to establish silk factories in Mount Lebanon.

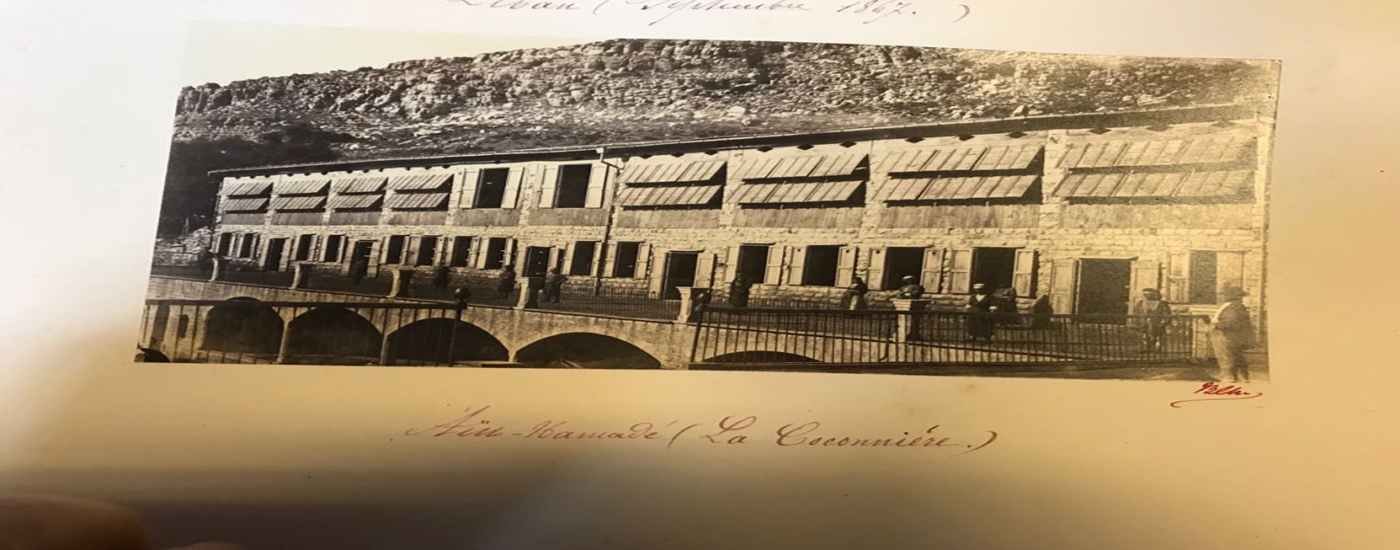

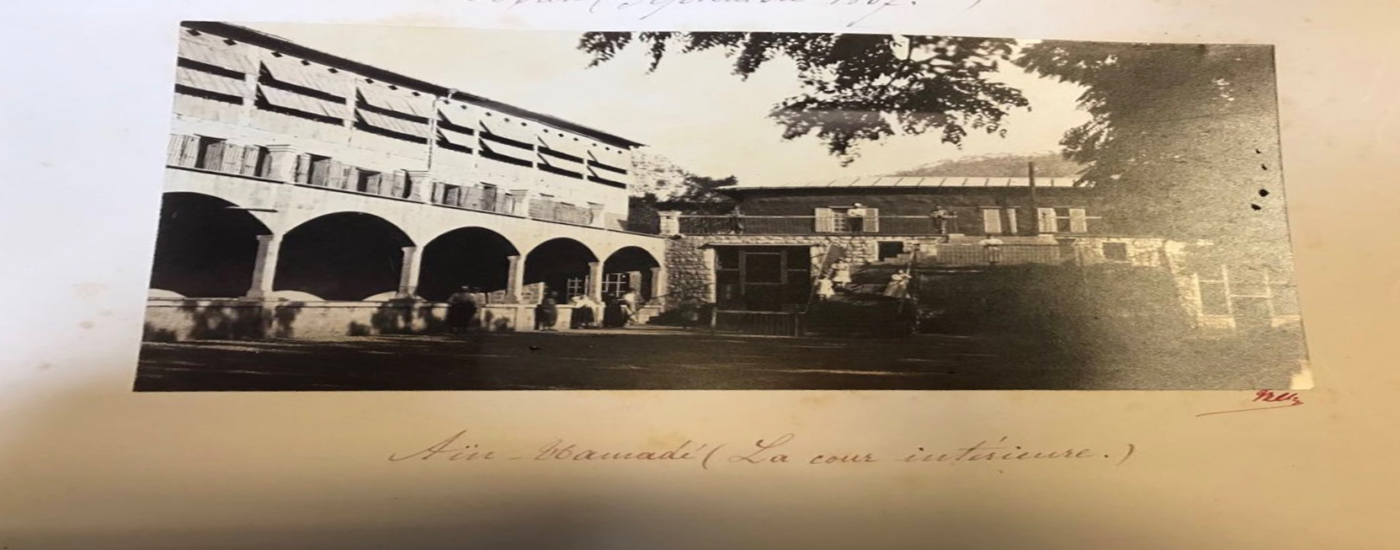

By 1851, the number of European filatures had increased by six. A French merchant, Andre de Figon, established two factories: one in Ghazir, Kisrawan, and another in Al-Qrayye in the Metn district. Another entrepreneur, with an inflated sense of self-importance that led him to change his name from Thomas Dalgue-Mourgue to Mourge d’Algue, established a sizable factory in “Ain Hamada”. Some Lyonnaise silk manufacturers followed suit and set up factories in Hammana.

This sudden rush by French capitalists and merchants resulted from the success of the Portalis experiment in manufacturing medium-to-high quality silk thread at low costs. Profits from such an enterprise were obviously higher in an area where wage labor was much cheaper than in Europe. In 1851 a male Lebanese worker was paid 4 to 5 piasters for a day’s work, while women were paid only 1 piaster for the same amount of work. In comparison, French men working in silk factories in the Midi received almost 8.8 piasters each work day and French women spinners received 4 piasters.”

Inventing Home: Emigration, Gender, and the Middle Class in Lebanon, 1870-1920, By Akram Fouad Khater

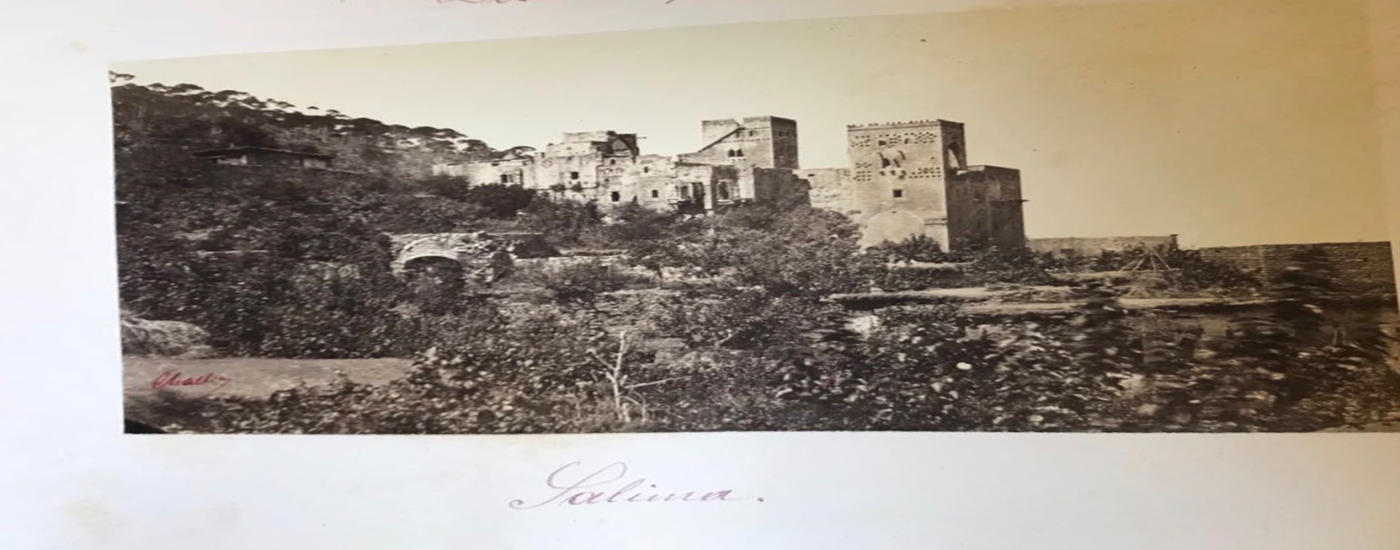

The Village of Arbanieh

Arbanieh, a village with origins dating back to the 6th century, derives its name from the Syriac language, meaning “a group of people who came together.” The village has a rich historical background, having been targeted by two Mamluk campaigns in the late 13th and early 14th centuries, resulted in significant loss of life and devastation, with only a fraction of the population surviving.

In 1846, Arbanieh became home to the largest silk factory in the Middle East, significantly impacting the village’s prosperity. This factory thrived in 1851 under the French Mourgue d’Algue, located in the part of the village known as Hamada.